Menu

Wetlands

Interested in having Jeanette Stewart come and present Wetlands? Please contact Sue Cournoyer for information and booking.

This page gives an overview of the educational story, Wetlands, with examples of the illustrations. This overview shows a small selection from the illustrations and explains some but not all of the points covered in the story. They also give you a glimpse of the discussions that arise as the story is being presented.

There is lots of room for interaction but the storyteller has an agenda and will direct the discussion to make certain important topics are covered.

Now, lets meet the educational team!

- 27 illustrations

- Presentation time - 1.5 hours

- Hands-on activity - Conservation project creation of a bog, sponge garden, or wetland-type environment if conditions permit, restoration of a natural wetland if one exists on the school property.

Join the educational team in the telling of this interactive story about wetlands.

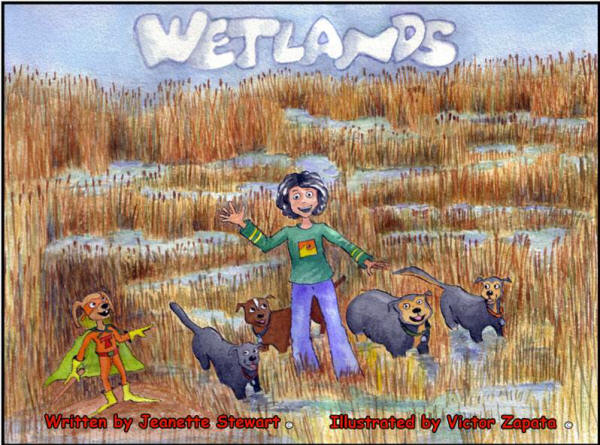

This story begins when Jeanette takes Rosie, Jack, EZ and Timo for a walk in a neighboring park. This park follows a local stream and is, in fact, a wetland. It provides the setting for a great adventure! Discussion about wetlands accompanies this illustration. What is a wetland? Notice Timo! He will introduce Spanish words throughout the story.

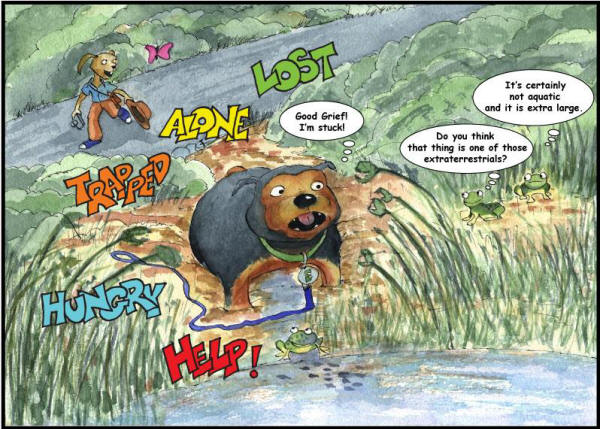

EZ stops to eat from a trash can and falls behind. Not knowing where Jeanette and her other companions are, she ventures off the trail only to become stuck in the soft, wet soil of the wetland. She panics and cries out for help, but to no avail, for Jeanette is far down the trail and has no idea EZ is missing. The definition of a terrestrial ecosystem is explained. What are the differences in a terrestrial ecosystem and a wetland ecosystem? How are they similar?

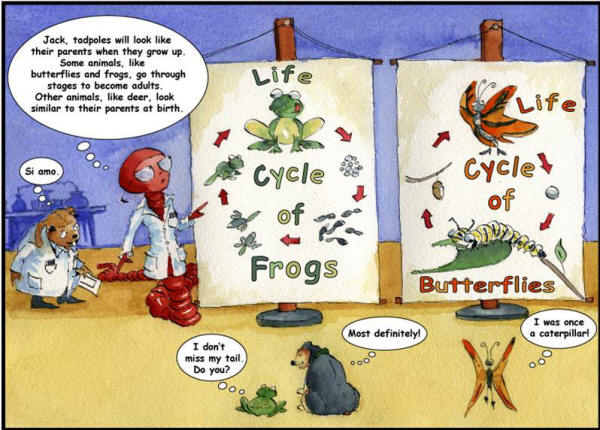

Curious Jack explores every puddle he can find, and students learn along with him about life cycles and how some animals go through stages to become adults while others are similar to their parents at birth. Discussion follows about life cycles. Do humans go through stages like the frog? In what ways do animals that have life cycle stages differ in their different stages? For example,do tad poles eat the same things as frogs?

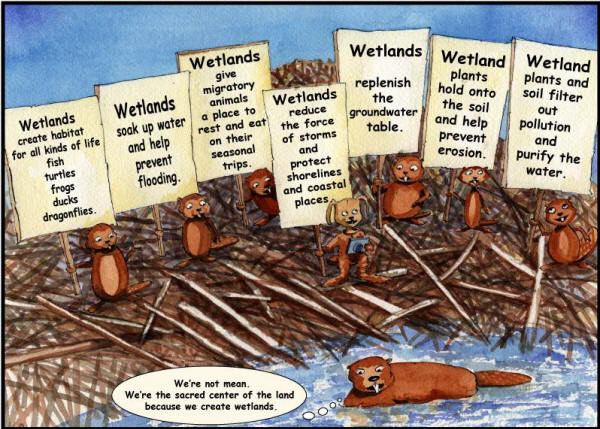

Rosie gets in big trouble when she picks a fight with some beavers. The beavers are really insulted when she calls them mean. They defend their reputation by claiming to be the sacred center of the Earth because they create wetlands. In fact, beavers were considered sacred by the North American Indians for just that reason. This illustration covers the most important services wetland provide.

We chose beavers as our example of a wetland animal. Students learn about physical and behavioral adaptation and discuss ways humans have adapted to their environment and give examples of other physical adaptations for other species.

Finally, Jeanette realizes EZ is missing. The little group retraces their steps and finds EZ still stuck. She is in a panic because the plants around her seem to be trying to eat her. The plants are Venus fly traps. We use this plant to teach about the adaptation of plants to their environment.

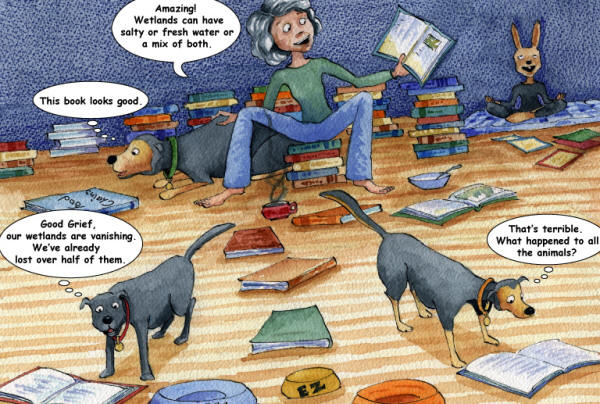

After freeing EZ, Jeanette and her friends return home exhausted. Everyone becomes interested in wetlands and spends lots of time reading and talking about wetlands. We use this illustration to teach about salt water, fresh water, and mixed water wetlands. The Chesapeake Bay is an estuary which is a mix of salt and fresh water. Students learn that wetlands are one of the richest ecosystems on Earth, comparable to a tropical rain forest. They learn about the dramatic loss of wetlands here in the United States and globally and the need to conserve these very rich ecosystems.

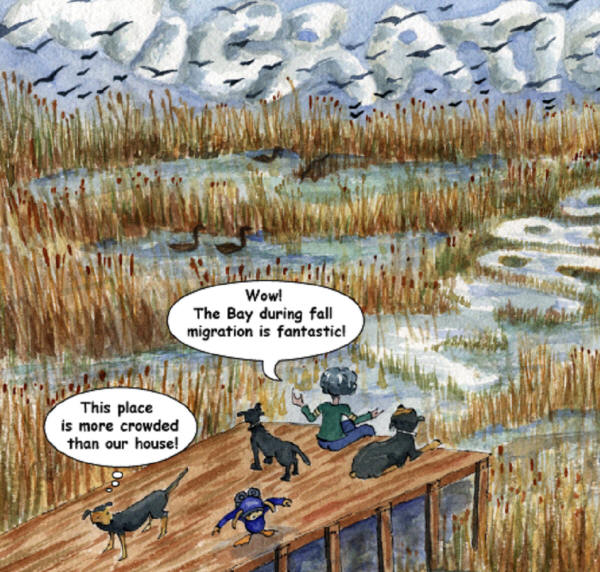

Jeanette has a big treat for her pets. They are going on a road trip to visit the Chesapeake Bay during fall migration. Here the students learn about marsh wetlands. Marsh wetlands are different from the first wetland they encountered in the story. The first wetland was a swamp wetland. Now the little group is going to see a marsh wetland. Students are encouraged to figure out the differences in these two wetland ecosystems by examining this picture and comparing it with the first pictures. Migration is discussed along with the importance of wetlands for migratory animals. Students also learn that some migratory animals learn the migratory route from their parents while other know the route instinctively from birth.

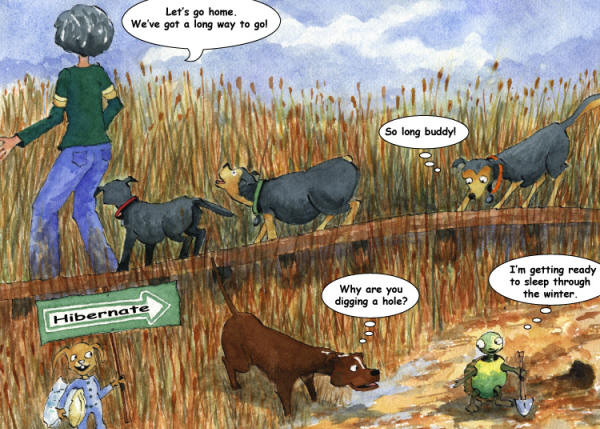

This illustration teaches another way animals adapt to the changes of seasons: hibernation. Notice a new character has been added to the story. She is an adopted stray and her introduction into the story really engages the students even further.

The next adventure Jeanette has takes us back to the first wetland, the swamp wetland. Upon arriving, everyone notices the beavers are leaving. Here the students learn about the degradation of wetlands and the impact pollution has on beavers and their habitats.

Once again Jeanette and friends encounter a problem. What can be done to help? Jeanette finds the answer when she contacts The Chesapeake Bay Program and learns about a workshop on creating and conserving wetlands. They attend the workshop and together with a lot of eager students our little group restores a wetland.

The hands-on component of this story is the creation of a wetland type environment or if possible the restoration of a wetland. This may appear to be a very ambitious undertaking but can be achieved on many school properties by capturing and collecting storm water runoff. The habitat created would probably resemble a marsh more than a swamp. It would serve to illustrate the type of plants and wildlife found in wetlands. It could also be created with different levels of water to demonstrate the different plants that are adapted to different water levels of water within the same wetland. Growing underwater grasses is another activity students can participate in. After the grasses mature, students travel to the Chesapeake Bay or smaller bay closer to the school to plant them.

These projects are extensive and require planning and patience but provide great opportunities for learning and satisfaction. They teach conservation techniques to students, encourage environmental stewardship, and give them a way to apply what they have learned and participate in a conservation project related to the health of their local watershed and the Chesapeake Bay.

These conservation projects are essentially living classrooms and are exactly that - living. They will grow and change over time just like the students who work with them. They help students connect to the larger world they live in. They allow students to collect information first hand and to draw their own conclusions from these first hand experiences. They awaken all the senses- not just visual and auditory. They encourage creativity, problem solving and observation skills. Lastly and for us at LANDS and WATERS most importantly, living classrooms promote a deep regard and respect for the natural world and all the living creatures with which we share habitat Earth.