Menu

Happenings in our Habitats

Interested in having Jeanette Stewart come and present Happenings in our Habitats? Please contact Sue Cournoyer for information and booking.

Part One of Three

This page gives an overview of the educational story, Happenings in our Habitats, with examples of the illustrations. This overview shows a small selection from the illustrations and explains some (but not all) of the points covered in the story. They also give you a glimpse of the discussions that arise as the story is being presented.

There is lots of room for interaction, but the storyteller has an agenda and will direct the discussion to make certain important topics are covered. As with all stories, the storyteller adjusts the amount of information presented to fit the age of the audience. Happenings in our Habitats has been presented successfully to students from 1st to 6th grades.

Now, lets meet the educational team!

- 31 Illustrations

- Presentation time - 2.5 hours for the entire story

- Hands-on activity - Creation of a wildlife habitat (options: pollinator garden, edge, woodland, bog, sponge garden, meadow)

Join the educational team in the telling of this interactive story about the watersheds.

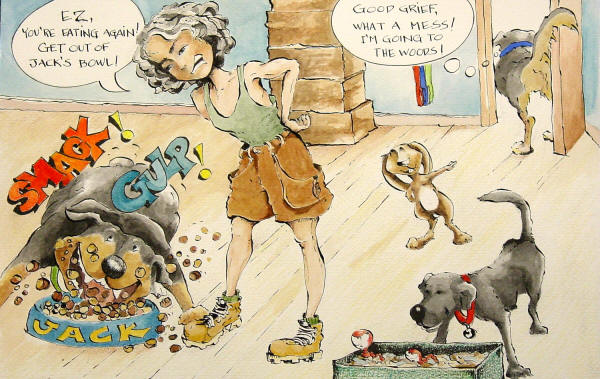

The story begins in Jeanette's crazy little one - bedroom apartment. EZ is eating again; Jack is getting into the worm bin. Jeanette's old dog Rosie goes in search of some peace in her favorite place, the woods! Jeanette, EZ, Timo, and Jack join her for an afternoon of fun.

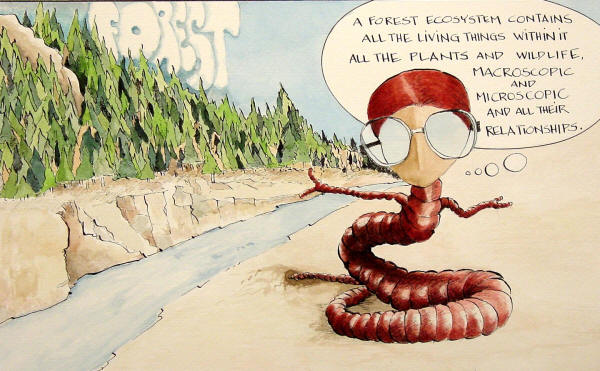

Students learn the concept of ecosystems (what they are and how they function). On the walk to the woods, Jeanette and her dogs encounter two types of environments, suburban and urban. Most students are familiar with these environments.

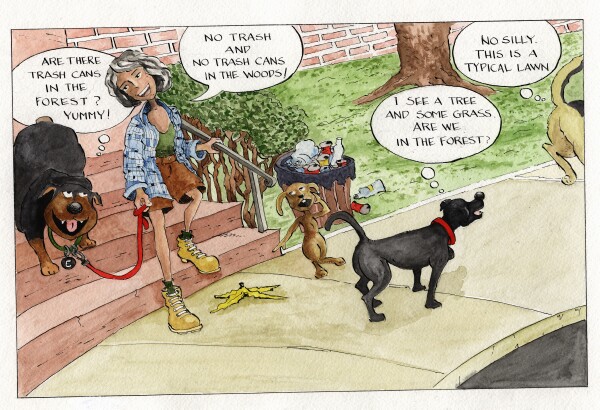

Discussion of suburban settings follows. Is the school in a suburban environment? Are their homes in a suburban setting? How might this environment be different from the forest ecosystem? Who created this setting? What other living things might live in a suburban habitat besides humans?

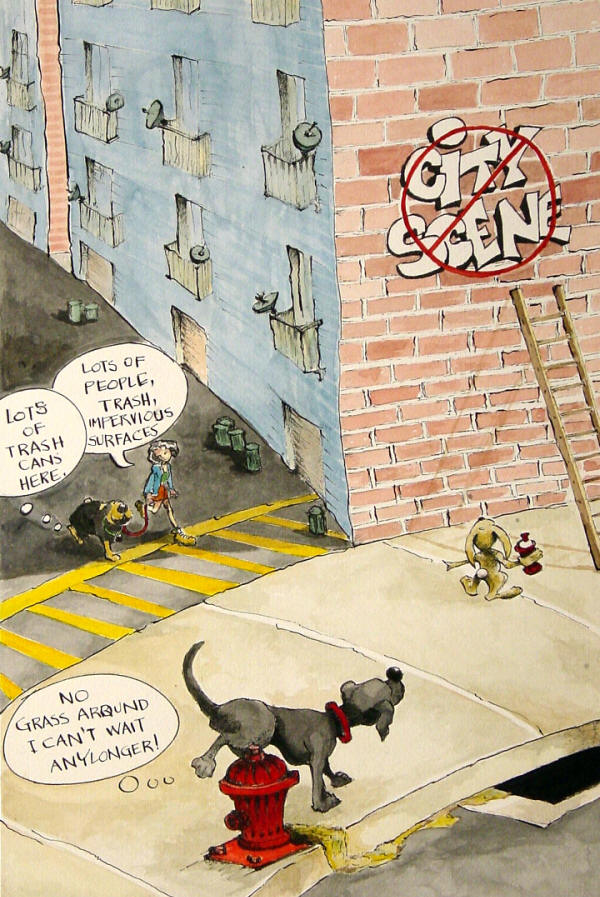

With this illustration, the lesson turns into a conversation about an urban environment. In what ways is an urban environment different from a suburban setting? Forest setting? Why isn't there trash in the forest? Why is there trash here?

The concept of pervious and impervious surfaces is introduced. Students are asked to give examples of impervious and pervious surfaces.

Students always notice Jack in this picture. We have taken an unconventional approach to explain how liquid and solid materials run off impervious surfaces into storm drain systems. What is a storm drain? Lots of discussion centers around this topic. Where do the materials that go down storm drains go? Are they being cleaned up before they reach the local stream? Are there any storm drains on the school property? What kind of materials might flow into these storm drains? (A field trip to identify and locate storm drains on school grounds and to find examples of impervious and pervious surfaces takes place at the end of part one.)

At this point, students begin looking at the land around them with a different perspective. Human impact on the natural world becomes more obvious as we discuss plant diversity, wildlife habitat, changes in exposed earth surfaces, hydrology, and temperature. This story combined with field trips outside help students connect with the land and water in the world around them. They are not merely moving through the outside world on their way to another activity; they are not studying it from pages in a book; they are experiencing it, observing it, and trying to figure out what it really is, how it functions and why it functions as it does.

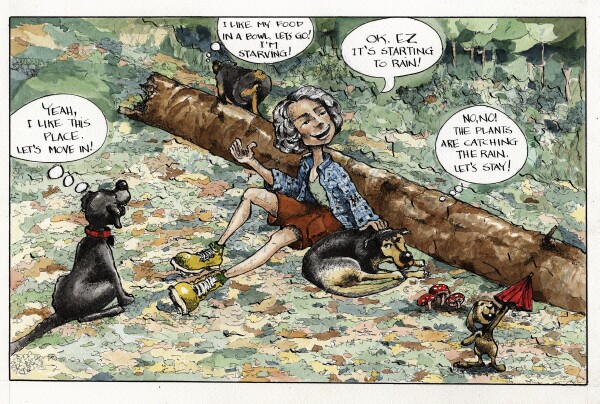

Finally in the forest, the characters being to talk about how different this setting is from a suburban or urban setting. Students join in for this opportunity to talk about the differences and similarities in the three environments.

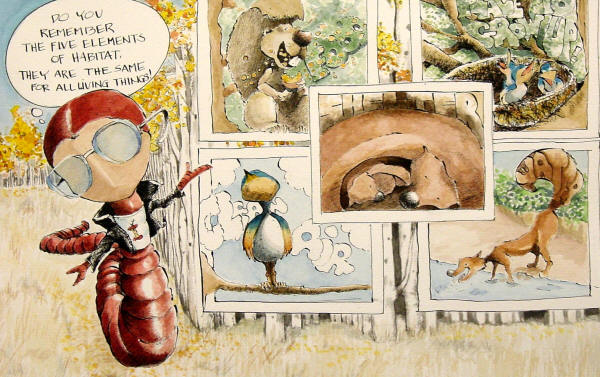

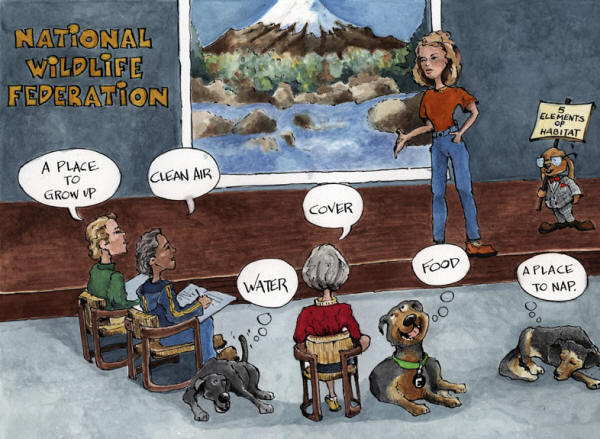

Wise worm reviews with the students the five elements of habitat.

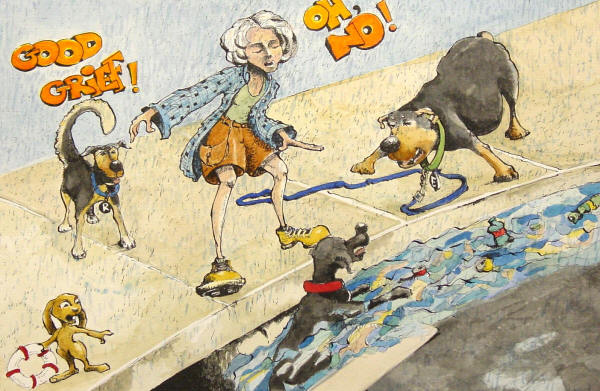

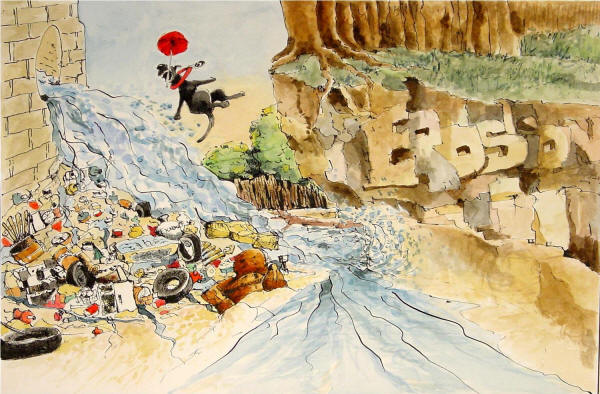

It begins to rain and the little group begins their journey home. The rain stormwater runoff has gathered like a river along the side of the road and is moving fast towards the storm drain. Jack gets caught up in this river of runoff!

There's lots of discussion with this last illustration. Why is there a river of runoff? Where is Jack going? What is going to happen to Jack? We encourage teachers to bring students outside during rain events at least once to observe what happens to rain as it runs off the school's property. Which surfaces appear to be absorbing rain, which are not? What is happening around the school's storm drains? Is there a problem with soil erosion? Are there places the water is pooling and forming wet areas? How long is the area wet? (This observation may help students locate an appropriate place for a bog or sponge garden, or even a wetland-type environment for their hands-on conservation project.) Where is the water from the roof going?

We ask students to write an end to this episode and include an illustration of their own! Before beginning part two, some of the students have an opportunity to share their stories and illustrations with the class.

Part Two of Three

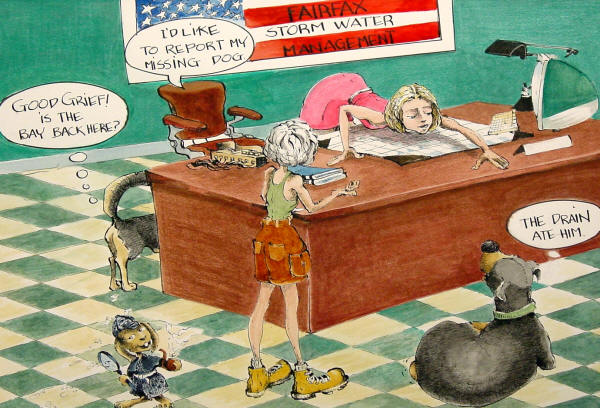

Part two begins with Jeanette, Rosie, and EZ visiting the Storm Water Management Division of Fairfax County to recover Jack from their lost and found box. After all, Jack was pulled into the storm drain system, so the people who manage the system must have him! Much to everyone's surprise, the clerk informs Jeanette that Jack is heading for the Chesapeake Bay. Here begins a discussion of how storm drain systems function, watershed and the Chesapeake Bay. Students learn what a watershed is and that we all live in a watershed.

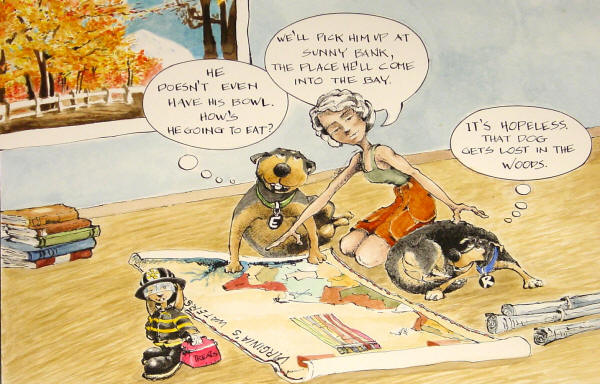

The dogs and Jeanette return home and find a map of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. Determined to find Jack, they locate the place where Jack will come into the Bay. Discussion of the school's local watershed takes place with this illustration. It includes an investigation to find the stream that receives the storm water from the school's property, identification of the stream and rivers the water flows into and the sub-watershed in which the school is located. The students work their way up to the largest watershed to which the school belongs. For schools in the Washington D.C area, the largest watershed is the Chesapeake Bay Watershed.

Before Jeanette, EZ, and Rosie leave to rescue Jack, Jack appears at the door in such a mess. He is covered with sand, oil, and trash and smells terrible. Students try and figure out what has happened to Jack.

Jack shares his dreadful experiences traveling through drain pipes and being thrust out into a local stream. His tale accurately details the degraded condition of streams in developed areas. Jack is not only a mess, he is angry. How could humans let this happen? The stream environment is so important and healthy streams are essential for a healthy watershed. Something must be done! But what?

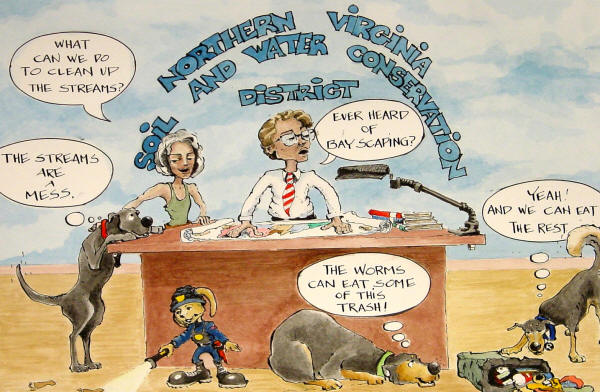

Jeanette finds solutions at the local Soil and Water Conservation District. There she learns about BayScaping, landscaping for the health of the Chesapeake Bay. Armed with lots of information, she returns home to learn about BayScaping. Information on BayScaping is covered.

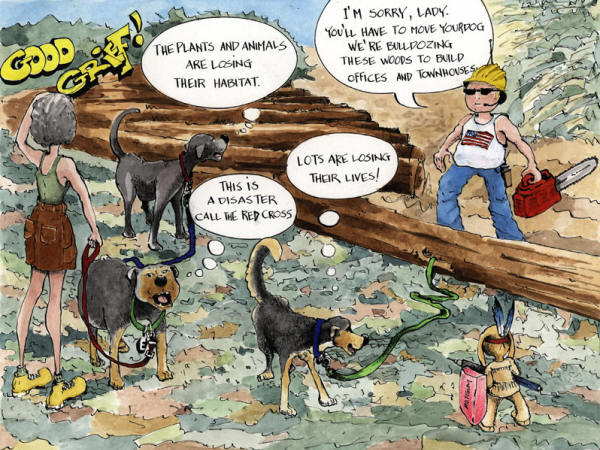

Unbeknown to Jeanette, Rosie wanders off to visit the woods and there she is horrified to find the trees being bulldozed down! Students must look carefully at the last illustration in this section and explain why Rosie is in grave danger.

Students are asked to write and illustrate the end of the story. What happens to Rosie? What will happen to the animals in the woods? At the end of this section, students walk the school property and describe how the land around the school might be affecting the local streams and consequently the Bay. Some of the observations should include trash on the grounds, motor car pollution from parking lots and roads, soil erosion, condition of the storm drains, and the amount of impervious surface cover. Are there any opportunities to correct the negative impacts by creating BayScaped areas on the grounds?

Part Three of Three

Part three begins when Jeanette realizes that Rosie is missing and wonders where she is. Jack gives her a hint, and they walk to the woods to find Rosie. They find Rosie and are so sad to see what is happening to the woods. All the plants will be lost and the animals are losing their habitat. Once again, Jeanette and her friends must try and find a way to help. What can they do to replace some of the habitat lost?

Jeanette finds help from National Wildlife Federation. She and her friends learn how to create wildlife habitat by planting native plants, building rock and brush piles, and creating water sources to provide the five elements of habitat. Students review the elements of habitat and discuss the possibilities for creating a wildlife habitat on their school grounds.

Jeanette is joined by EZ, Rosie, Jack, Timo and friends to develop a wildlife habitat in Jeanette's back yard. Even the construction crew joins in and helps. Many of the plants from the woods are rescued and planted in the new habitat.

Students begin investigating native plants and help draw up a list of possible plants for the school's habitat. They must consider such factors as light, water and soil conditions, wildlife value of the plants (food, shelter, and cover). They also must address the problem of providing a water source year round.

The hands-on component of this story is the creation of a wildlife habitat or a garden to address storm water run off. The choices include a pollinator garden, bog or sponge garden, woodland garden, edge garden, riparian buffer zone, and meadow garden. These projects are extensive and require planning and patience but provide great opportunities for learning and satisfaction. They teach conservation techniques to students, encourage environmental stewardship, and give them a way to apply what they have learned and participate in a conservation project related to the health of their local watershed and the Chesapeake Bay.

These conservation projects are essentially living classrooms and they are exactly that - living. They will grow and change over time just like the students who work with them. They help students connect to a world much larger than the human world. They allow students to collect information first hand and to draw their own conclusions from those first hand experiences. They awaken all the senses- not just visual and auditory. They encourage creativity, problem solving and observation skills. Lastly and for us at LANDS and WATERS the most important, living classrooms promote a deep regard and respect for the natural world and all the living creatures with which we share habitat Earth.